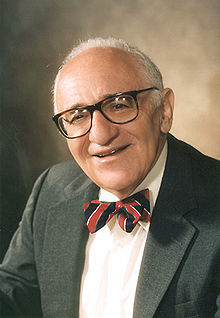

Murray Rothbard

| Murray Newton Rothbard | |

| |

| Personal Details | |

| Birth: | March 2, 1926 Bronx, New York, USA |

| Death: | January 7, 1995 (aged 68) |

| Education: | Columbia University |

| Occupation: | Economist, Author |

| Party: | Libertarian Party (1974-1989) Peace and Freedom Party (prior to 1974) |

| view image gallery | |

| view publications | |

Murray Newton Rothbard (March 2, 1926—January 7, 1995) was an American economist, historian and natural law theorist belonging to the Austrian School of Economics who helped define modern libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism. He was son of David and Rae Rothbard. On January 16, 1963, he was married to JoAnn Schumacher in New York City.

Life

Early Life (1950s-1970s)

Rothbard was born into a Jewish family in the Bronx. "I grew up in a Communist culture," he recalled. [Raimondo p 23] He attended Columbia University, where he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree (1945), a Master of Arts degree (1946), and a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1956.

In the course of his life, Rothbard was associated with a number of political thinkers and movements. During the early 1950s, he studied with the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises and began working for the William Volker Fund. During the late 1950s, Rothbard was briefly an intimate of Ayn Rand and Nathaniel Branden. In the late 1960s, Rothbard advocated an alliance with the New Left anti-war movement, on the grounds that the conservative movement had been completely subsumed by the statist establishment. However Rothbard later criticized the New Left for not truly being against the draft and supporting a "People's Republic" style draft. It was during this phase that he associated with Karl Hess and founded Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought with Leonard Liggio and George Resch, which existed from 1965 to 1968. From 1969 to 1984 he edited the Libertarian Forum, also initially with Hess (although Hess' involvement ended in 1971. In 1977, he established the Journal of Libertarian Studies, which he edited until his death in 1995.

Libertarian Activism, later career (1970s-1980s)

During the 1970s and '80s, Rothbard was active in the Libertarian Party. He was frequently involved in the party's internal politics: from 1978 to 1983, he was associated with the Libertarian Party Radical Caucus, allying himself with Justin Raimondo, and Bill Evers and opposing the "low tax liberalism" espoused by 1980 presidential candidate Ed Clark and Cato Institute President Edward H Crane III. He split with the Radical Caucus at the 1983 national convention, and aligned himself with what he called the "rightwing populist" wing of the party, notably Ron Paul, who ran for President on the LP ticket 1988. In 1989, Rothbard left the Libertarian Party and began building bridges to the post-Cold War right. He was the founding president of the conservative-libertarian John Randolph Club and supported the presidential campaign of Pat Buchanan in 1992. However, prior to his death in Manhattan of a heart attack, Rothbard had become disillusioned with the Buchanan movement.

He was buried in Virginia where his wife's family resided.

Other Works

In addition to his work on economics and political theory, Rothbard also wrote on economic history. He is one of the few economic authors who have studied and presented the pre-Smithian economic schools, such as the scholastics and the physiocrats. These are discussed in his unfinished, multi-volume work, An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought.

Rothbard opposed what he considered the overspecialization of the academy and sought to fuse the disciplines of economics, history, ethics, and political science to create a "science of liberty," as reflected in his many books and articles. His approach was influenced by the arguments of Ludwig von Mises in such books as Human Action and Theory and History that the foundations of the social sciences are in a logic of human action that can be known prior to empirical investigation. Rothbard sought to use such insights to guide historical research, especially in his work on economic history, but also in his four-volume history of the American Revolution, Conceived in Liberty.

He was the academic vice president of the Ludwig von Mises Institute and the Center for Libertarian Studies (which he founded in 1976), was a distinguished professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and edited the Rothbard-Rockwell Report with Lew Rockwell.

Anarcho-Capitalism

The Libertatis Æquilibritas is one symbol used by anarcho-capitalists.In 1949 Rothbard concluded that the free market could provide all services, including police, courts, and defense services better than could the State. He was now officially an anarcho-capitalist. Rothbard described the moral basis for his anarcho-capitalist position in two of his books, For a New Liberty, published in 1972, and The Ethics of Liberty, published in 1982. He described how a stateless economy would function in his book Power and Market.

Rothbard proclaimed the right of self-ownership, that each person owned himself, and the right to private property, that each person owned the fruits of his labor. Accordingly, each person had the right to exchange his property with others. Rothbard defined the libertarian position through what is called the non-aggression principle, that "No person may aggress against anybody else." Rothbard attacked taxation as theft, because it was taking someone else's property without his consent. Further, conscription was slavery, and war was murder. Rothbard also opposed compulsory jury service and involuntary mental hospitalization.

Rothbard's Law

Rothbard's Law is a self-attributed adage. In essence, Rothbard suggested that an otherwise talented individual would specialize and focus in an area at which they were weaker -- or simply flat out wrong. Or as he often put it: "everyone specializes in what he is worst at."

In one example, he discusses his time spent with Ludwig von Mises,

In all the years I attended his seminar and was with him, he never talked about foreign policy. If he was an interventionist on foreign affairs, I never knew it. This is a violation of Rothbard's law, which is that people tend to specialize in what they are worst at. Henry George, for example, is great on everything but land, so therefore he writes about land 90% of the time. Friedman is great except on money, so he concentrates on money. Mises, however, and Kirzner too, always did what they were best at. Continuing on this point,

There was another group coming up in the sixties, students of Robert LeFevre's Freedom School and later Rampart College. At one meeting, Friedman and Tullock were brought in for a week, I had planned to have them lecture on occupational licensing and on ocean privatization, respectively. Unfortunately, they spoke on these subjects for 30 minutes and then rode their hobby horses, monetary theory and public choice, the rest of the time. I immediately clashed with Friedman. He had read my America's Great Depression and was furious that he was suddenly meeting all these Rothbardians. He didn't know such things existed.

Books

- America's Great Depression

- An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (2 vol.)

- The Case for the 100 Percent Gold Dollar

- The Case Against the Fed

- The Complete Libertarian Forum (2 vol.)

- Education: Free and Compulsory

- Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays

- The Ethics of Liberty

- Freedom, Inequality, Primativism, and the Division of Labor

- For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto

- Conceived in Liberty (4 vol.)

- History of Money and Banking in the United States

- Individualism and the Philosophy of the Social Sciences

- Irrepressible Rothbard: The Rothbard-Rockwell Report Essays of Murray N. Rothbard

- Logic of Action (2 vol.)

- Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero

- Making Economic Sense

- Man, Economy, and State

- The Panic of 1819

- Power and Market

- Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy

- What Has Government Done to Our Money?

|

GFDL |

This article is based on a Wikipedia article and is controlled by version 1.2 or later of the the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL).

|

- 1926 Births

- 1995 Deaths

- Biographies

- Infoboxes with birth information

- Wikipedia Based Articles

- Economists

- National Party LNC Members (Not specified)

- Libertarian Party Radical Caucus Leaders

- Authors

- New York 1976 National Convention Delegates

- 1976 National Convention Delegates

- New York 1981 National Convention Delegates

- 1981 National Convention Delegates